Why the Internet No Longer Shows Everyone the Same World

How personalization quietly reshaped information, culture, and public discourse

Introduction

For most of its early history, the internet was experienced as a shared space.

People visited the same homepages. They saw the same front pages, trending lists, and popular links. While users chose which sites to visit, the structure of what was visible was broadly common. There was a sense — often implicit — that “this is what is happening online.”

That assumption is no longer true.

Today, two people can open the same platform at the same time and see entirely different worlds. Different news, different videos, different debates, different moods. The content itself may come from a shared pool, but what each person encounters is increasingly personalized, filtered, and ranked specifically for them.

This article explains what changed — not in terms of politics or culture wars, but in terms of system design. It describes how the internet moved from shared visibility to personalized visibility, what that shift means structurally, and why it quietly reshaped how people understand the world and each other.

No alarmism. No blame. Just the mechanics of a fundamental change.

The Internet Used to Be Mostly Shared

In the early web, most online experiences were organized around common reference points.

Large portals had front pages. News sites had headlines. Forums had visible threads ordered by time or popularity. Search engines returned roughly similar results for similar queries. While individuals navigated differently, the structure of what was visible was largely the same for everyone.

This created something like a shared informational environment.

People argued about the same stories because they encountered the same stories. Cultural moments emerged because large numbers of people were exposed to the same content at roughly the same time. Even disagreement happened inside a common frame.

This did not mean the internet was neutral, fair, or complete — but it was relatively legible. You could point to “what’s trending” or “what people are talking about” and have that phrase mean something concrete.

That architecture is what changed.

The Shift to Personalization

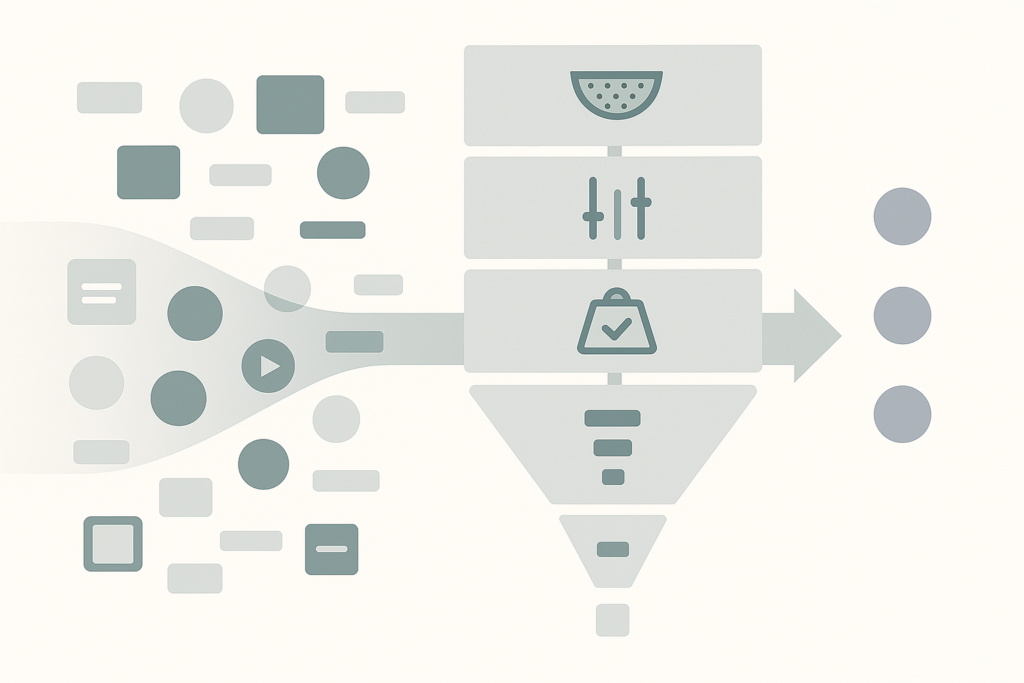

As platforms grew, so did the volume of content. The number of posts, videos, articles, and creators exploded far beyond what any human could manually navigate.

To manage this scale, platforms introduced ranking systems.

Instead of showing everything in simple chronological order, they began sorting content based on signals: what users clicked, watched, liked, shared, ignored, or returned to. The goal was not to change reality, but to reduce overload and increase relevance — to show each person what they were most likely to find useful, interesting, or engaging.

Over time, this logic became more sophisticated.

Modern platforms no longer ask, “What should we show everyone?”

They ask, “What should we show this person, right now?”

The result is personalization.

Not a different internet for every user — but a different view into the same internet, shaped by behavioral patterns and probabilistic predictions.

What “Personalized” Actually Means

Personalization is often misunderstood as content being created specifically for each individual. That is not what usually happens.

Instead:

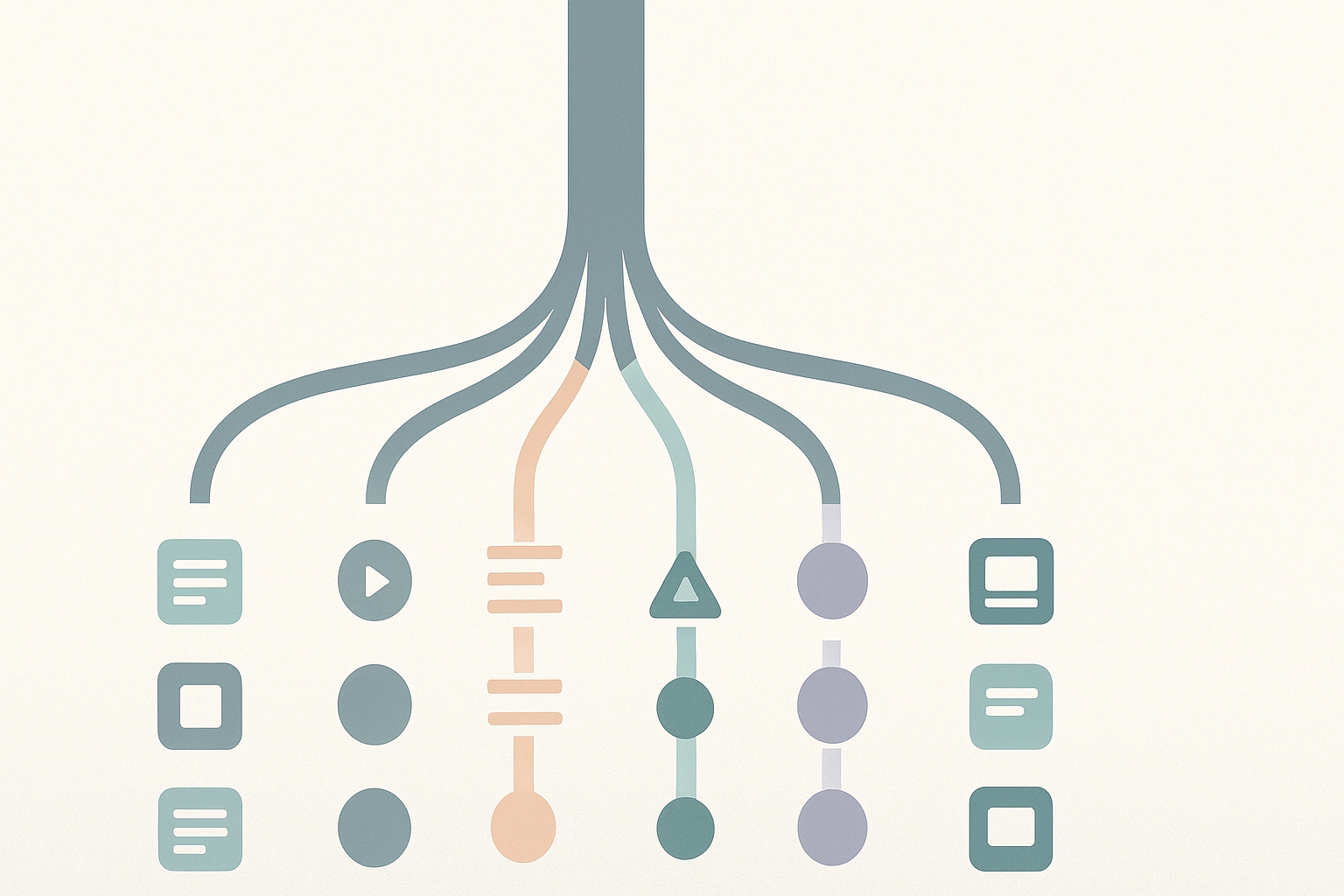

- Platforms maintain a very large shared pool of content.

- Ranking systems decide which subset of that pool to show to each user.

- The order, timing, and selection differ from person to person.

Think of it as one enormous library with billions of items — and millions of different librarians, each arranging a slightly different shelf for each visitor.

Two users may technically have access to the same material, but in practice they encounter different slices of it, presented in different sequences, framed by different surrounding content.

Over time, this creates diverging informational paths.

How This Changes Perception of Reality

Human perception is shaped by what is visible.

People intuitively assume that what they see is representative — that their experience reflects something about the broader world. When visibility diverges, so do intuitions about what is normal, important, common, or rare.

If one person repeatedly encounters stories about innovation, they may feel the world is accelerating.

If another mostly sees stories about conflict, they may feel the world is deteriorating.

If a third mostly sees entertainment, they may feel the world is light, playful, or trivial.

None of these perceptions are necessarily wrong. But they are partial.

When different people live inside different informational streams, they not only disagree — they often fail to recognize that they are reacting to different inputs in the first place.

This is how fragmentation emerges quietly, without anyone explicitly choosing it.

Why This Is So Hard to Notice

One reason this shift is difficult to perceive is that it happened gradually.

There was no moment when the internet officially became “personalized.” There was no announcement, no clear before-and-after boundary. Ranking systems were introduced incrementally, refined continuously, and adapted invisibly.

From the user’s perspective, the experience simply became more convenient.

Content felt more relevant. Feeds felt more engaging. Recommendations felt more accurate. The system adapted around the user so smoothly that the underlying change in structure was rarely visible.

And because each user only sees their own version, there is no direct way to compare experiences unless people intentionally do so.

The personalization layer is, by design, quiet.

This Is Not Good or Bad — It Is Structural

It is tempting to treat this shift as either a problem or a solution.

But structurally, it is neither.

Personalization solves real issues: information overload, discovery, relevance, and scale. Without it, modern platforms would be unusable.

At the same time, personalization introduces new tradeoffs: reduced shared context, increased fragmentation, and the loss of common reference points.

These are not moral failures. They are design consequences.

Every system optimizes for something. When visibility is optimized for individual relevance, collective coherence becomes a side effect rather than a goal.

Understanding that tradeoff is more useful than judging it.

Why Understanding This Matters

This structural shift affects:

- How people interpret news and culture

- Why misunderstandings escalate so easily

- Why groups drift apart even without intending to

- Why “everyone sees something different” is no longer just a metaphor

Understanding the mechanics behind this helps people:

- Communicate more carefully

- Interpret disagreement more generously

- Design better systems and policies

- Develop healthier expectations about online discourse

Most importantly, it restores a sense of perspective.

When people realize that others are not just disagreeing — but inhabiting different informational environments — conversations can become more grounded, more patient, and more constructive.

Conclusion: From a Shared Internet to Overlapping Worlds

The internet did not become personalized because someone wanted to fragment society. It became personalized because the scale of information demanded new ways of filtering and organizing content.

The result is not one broken world — but many overlapping ones.

Each shaped by algorithms, signals, and feedback loops. Each coherent from the inside. Each incomplete from the outside.

Recognizing this does not solve every problem. But it clarifies the terrain.

And clarity, in complex systems, is often the first and most important step.